To close out this year's Subchaser Archives Notes, I thought I'd offer some notes on my take on the effectiveness of the U.S submarine chasers in WWI.

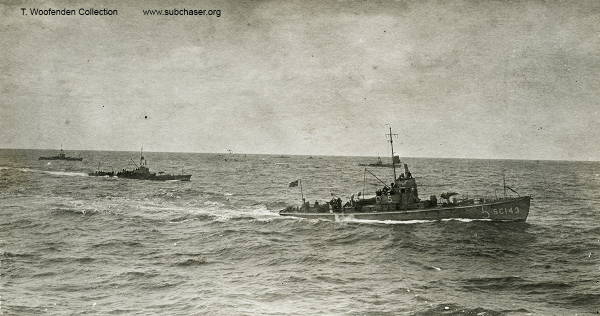

As a backdrop, there were many stories at the time, of sub kills by chasers. One of these is in an article series, scans of which are posted this month: Captain M.S. Brown offers an exciting, three-part account of his experiences on the chasers, including an account of a submarine kill by SC 177 and SC 143. (See link below to the articles.)

In the author's account, published in Pacific Motor Boat magazine in 1919/1920, a long pursuit with multiple encounters ended with the chasers dropping depth charges and pieces of the submarine floating to the surface; and the chasers receiving credit for a kill.

Submarine chaser SC 143 underway. T. Woofenden Collection.

But the official record of this pursuit, which took place on 30 May, 1918, has a different ending: After the depth charges were dropped, Listeners again detected the sound of the submarine, moving away, and no further sound contact was made. (See Appendix II, pages 184-185, Hunters of the Steel Sharks: The Submarine Chasers of WWI.)

I propose that there are two takeaways from this story: First, always be skeptical of submarine kill stories. For every confirmed kill, there are a dozen claims of kills, and newspapers and magazines were anxious to publish a good story. Just among the pursuit accounts by submarine chasers, there are many stories where the official record clearly shows no kill, but the story that makes it into print is a confirmed kill -- sometimes with added nuggets such as the submarine being brought to the surface later, or U-boat crewmen committing suicide while submerged, or pieces of the sub being retrieved.

But second and more important, we can't judge the effectiveness of the chasers by kill counts alone. The Navy certainly did not. The purpose of the barrage line was to block U-boats from entering the sea lanes and sinking ships. Hampering the U-boats with pursuits and attacks limited their ability to reach open seas, and for those that did make it past the barrage lines, reduced their available days at sea, thus reducing their effectiveness. The Navy's regard for the chasers was high, as evidenced not only in the remarks of men like Adm. Sims, but in the Navy's continued use of chasers into WWII.

See the epilogue in my book for a fulsome treatment of these arguments -- but in short, I would argue that pursuits and attacks like the one described in Capt. Brown's account should be celebrated, even without official credit for a kill. That 133 U.S. submarine chasers -- 100-foot motorboats with wood hulls and open-crankcase engines -- sailed overseas and participated in the advent of antisubmarine warfare is a remarkable fact on its own. It was an incredible effort, and the pursuits and attacks, chasers and other ASW vessels bottling up the U-boats and slowing their progress, stand as a fascinating story and an important element in the victory.

Best wishes for a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

--Todd Woofenden, editor

Added this month:

Scans of a three-story series, "The Experience of a Yankee Sub-Chaser", and two stories on "Life Overseas on the Yankee Sub-Chasers," by Capt. M.S. Brown, in Pacific Motor Boat (Vol. 11, No. 7; Vol.12, No 7; and Vol. 12, No. 8). Thanks for Ian Scales for sending the scans to The Subchaser Archives.